Perfect is Boring: Why We Trust Brands That Make Mistakes

We asked Richard Shotton, Method1's senior behavioral science partner, to provide a perspective on the "pratfall effect," a powerful behavioral science principle. Most brands avoid it for the very reason it works: it requires embracing imperfection. Drawing on decades of behavioral research and real-world applications, Richard reveals how acknowledging flaws can actually be a winning strategy—one that builds the irresistibility of your brand.

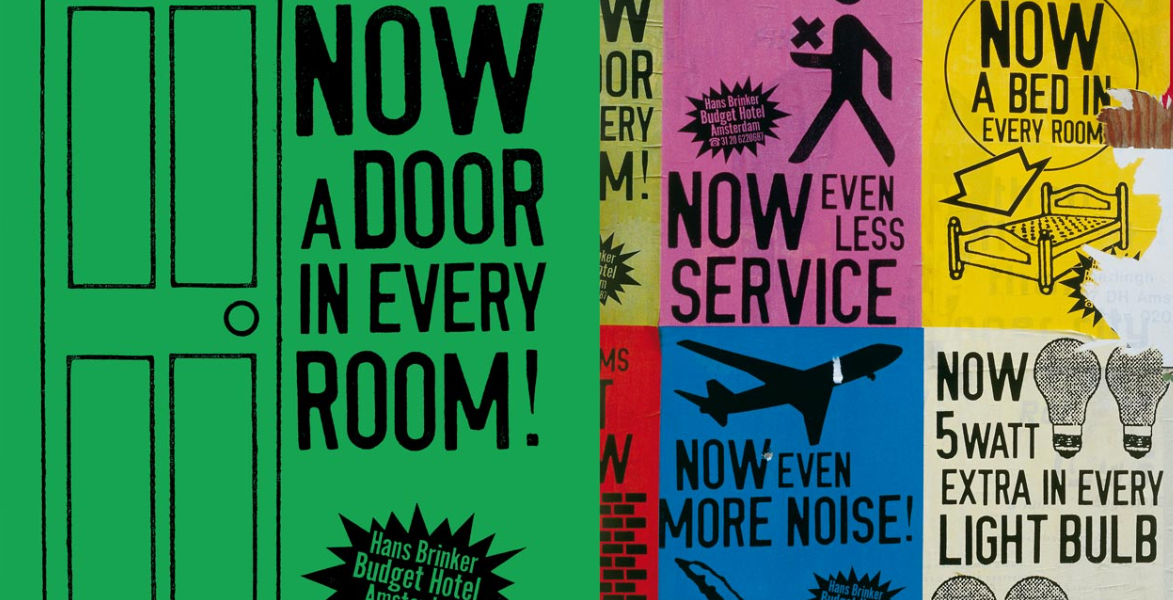

If you were lucky enough to visit Europe as a backpacking youth, among Amsterdam’s cobbled streets, whirring bikes and canals, you may have come across the now (in)famous Hans Brinker Hostel.

But only if you were on a tight budget.

It’s a cheap and cheerful place to lay your head, squarely aimed at a young, party-loving crowd. And since the 1990s, their ads have labelled the hostel as, “The Worst Hotel in the World,” highlighting all the things you won’t get. Like functioning elevators, a good night’s sleep, privacy. What you will get is a budget bunk in a super-central location.

Hans Brinker Hostel advertising campaigns (Shiji Group Review Pro Blog)

The campaigns lean into the terribleness of their establishment. On the face of it, a risky strategy. But Hans Brinker remains an ever-popular backpacker’s choice, so clearly, highlighting weaknesses works.

Let’s explore why.

Pratfalling in Love with a Brand

Hans Brinker isn’t the only brand to take this candid approach. Some of the most well-known brands have openly displayed shortcomings.

Take Listerine in the 1950s and 1960s. Rather than mask their mouthwash’s medicinal taste, they proclaimed it proudly: "The taste people hate—twice a day." You might think this commercial suicide. But even when more palatable options like Scope hit the market in the 1960s, Listerine remained the undisputed leader. Consumers had come to associate its harsh taste with efficacy. The very thing that might have killed the brand made it unbeatable.

Why is this approach so effective?

Psychological studies have found that we genuinely find people who admit weaknesses more appealing. It's called the “pratfall effect” and was first shown experimentally by Eliot Aronson in 1966.

For this study, Aronson recorded an actor answering a series of quiz questions.

The quizzer—fore-armed with the right responses—answered 92% of the questions correctly. After the quiz, the actor then pretended to spill coffee all over their new suit (a pratfall).

Aronson played the recording to two groups of participants: one group heard the recording with the pratfall included, and one heard only the quiz. When asked, people who’d heard the blunder rated the high-scoring contestant as 45% more likable than those who hadn’t.

So, showing a human side clearly boosts likeability. And modern brands have taken notice.

Oatly built its entire identity on self-aware messaging. With irreverent slogans like "Wow, no cow!" and packaging that pokes fun at itself, Oatly did something unusual. They acknowledged what skeptics were already thinking: that oat milk sounds like a terrible idea. That honesty made them impossible to dismiss—and led to a $10 billion IPO.

Or consider Guinness: "Good things come to those who wait." Yes, you have to be patient to get your pint, but that's because of its signature pour. Rather than apologize for this delay, Guinness made it part of the ritual. Those two minutes became proof you were getting something worth waiting for.

But does this mean any brand, at any time, can say something self-effacing and win market share?

Not quite.

In a twist to Aronson’s experiment, a separate group of participants heard the actor answering only 1 in 3 questions correctly. As before, half the participants heard the quizzer pretend to spill a cup of coffee.

This time—when the quiz performance was decidedly mediocre—the pratfall resulted in lower likeability. This suggests that the pratfall effect is only effective when people (or brands) are already seen as competent. It backfires if they don’t have enough kudos.

It matters that Listerine actually freshens your breath, that Oatly makes non-dairy life feel genuinely fun, and that a pint of Guinness is always worth the wait. For pratfalls to work, your brand can't already be failing.

That said, even if your brand has earned the right to stumble, there's another consideration.

Who reveals a flaw first matters.

It’s All About Trust

It’s not just about consumers liking you—it’s about building trust. Mistakes, if owned and well-handled, can enhance loyalty through generating a sense of openness and honesty. So if your brand has a flaw, or you do something wrong, it’s better to admit it upfront—before someone else does.

There’s a fascinating study demonstrating this practice—called the “stolen thunder effect”—carried out by Kipling Williams from the University of Toledo, and colleagues. Stolen thunder refers to a tactic whereby a defense attorney admits a weakness in their case before the prosecution points it out.

For the study, Williams recruited 257 participants and asked them to read one of three versions of a criminal assault trial. The accounts were all the same apart from the handling of a piece of evidence that made the defendant appear more guilty:

- In one account, the damaging evidence was brought up by the prosecution (thunder)

- In another, it was brought up first by the defense attorney, before being repeated by the prosecution (stolen thunder)

- In a third set-up, the damaging evidence was not revealed at all (no thunder)

Participants were asked about the likelihood of guilt on a scale from 1 to 9.

| Trial Version | Mean of Perception of Defendant's Guilt |

|---|---|

| Thunder – prosecution points out weakness | 6.61 |

| Stolen thunder – defense admits weakness | 5.83 |

| No thunder – weakness not revealed | 5.04 |

As expected, results showed that guilt was perceived to be lowest when the damaging evidence stayed hidden.

But it was also clear that people were 12% less likely to assign guilt when the damaging evidence was raised first by the defense, rather than waiting for the prosecution to use it.

The message is clear: if there’s a negative aspect of your brand, own it early. Waiting for someone else to expose your flaws will erode trust.

When a Flaw is Not a Flaw

So, admitting a weakness (while being competent) makes people like you more, and getting it out in the open first can generate trust. But as a brand, what should you own up to?

You need to give it some thought, because getting it wrong could undermine consumer confidence. If you’re an airline, for example, you wouldn’t want to claim a poor safety record.

We can be guided in this by a 2003 study from Gerd Bohner at Bielefeld University, Germany and colleagues, who explored the impact of the pratfall effect on attitudes towards a restaurant.

The researchers recruited 131 participants and split them into three groups. Each group saw an ad for the same restaurant.

- The first ad communicated only positive features (e.g., cozy atmosphere)

- The second described positive features (e.g., cozy atmosphere) and unrelated negative features (e.g., no dedicated parking spaces)

- The third ad contained negative features (e.g., small restaurant size, small selection of dishes) and related positive features (e.g., cozy atmosphere, fresh ingredients)

Participants rated their attitudes towards the restaurant on a scale of 1 to 9, lowest to highest.

Aligning with the pratfall effect, the results showed that publicizing only good stuff only was the worst approach—this ad scored lowest, at 4.29. Perhaps an overly polished brand feels too good to be true.

Impressions improved (4.51) when negative aspects, like no outdoor seating, were admitted. But the highest score—5.62—went to the restaurant when the ad supplied negative and related positive features. That’s an improvement of 31.2% compared to positive features alone.

Bohner argued that this was because connecting a positive and a negative feature is a great way to frame the negative in a better light. The restaurant may be small, but that only enhances the cozy atmosphere.

That’s why the Hans Brinker Hostel ads work so well. No, you won’t get your own room, let alone a turn down service—but that’s what makes it so cheap despite its fantastic location.

What You Can Do

In a world of curated perfection, admitting a flaw is an underused brand strategy. Some carefully crafted self-deprecation can go a long way towards buying good will and warmth, while lending your brand authenticity.

A premium brand that charges more than competitors might acknowledge this openly while explaining it's because they use ingredients others won't pay for. Limited distribution transforms from weakness to strength when it’s tied to selective partnerships—a commitment to only work with retailers who truly understand craft.

Perhaps your product has an intense flavor that might overwhelm some palates. Rather than hiding this, you might embrace it as proof you're made for those seeking something real.

Or maybe you're a smaller player who can't match the advertising spend of your competitors. That very limitation could become your calling card—evidence that every penny goes into the product itself, not billboards.

The take-homes here are clear.

- If you’re going to embrace the honest approach, be competent. Aronson’s study demonstrates that you have to earn the right to admit flaws before you do so.

- Own any public weakness or failing early on. Don’t wait for a competitor to reveal what could be seen as a problem. Getting in first displays transparency and builds trust.

- Like Hans Brinker, frame flaws with a positive flipside that can serve as an explanation. Hendricks may be “Not for everyone”—that’s because it’s a complex flavor for those with a discerning palate.

And finally, if you hadn’t come across Hans Brinker Hostel before and you’re planning a trip to Amsterdam—you have been warned.

To see behavioral principles in action making indulgence brands irresistible, explore Method1’s work.

About the Author

Richard Shotton, senior behavioral science partner to Method1, is the best-selling author of The Choice Factory and The Illusion of Choice, exploring how behavioral biases shape consumer decision making. He co-hosts the "Behavioral Science for Brands" podcast with M1 president MichaelAaron Flicker.

Richard is also the founder of Astroten (where he has advised brands like Google, Mondelez and BrewDog) and an honorary IPA fellow and associate at the Moller Institute, Churchill College, Cambridge University.

His latest book, Hacking The Human Mind: The Behavioral Science Secrets Behind 17 of the World's Best Brands (co-authored with Flicker) will be released on September 30, 2025 and is now available for pre-order.

References

Aronson, E., Willerman, B., & Floyd, J. (1966). The effect of a pratfall on increasing interpersonal attractiveness. Psychonomic Science, 4(6), 227-228.

Williams, K. D., Bourgeois, M. J., & Croyle, R. T. (1993). The effects of stealing thunder in criminal and civil trials. Law and Human Behavior, 17(6), 597-609.

Bohner, G., Einwiller, S., Erb, H-P., & Siebler, F. (2003). When small means comfortable: Relations between product attributes in two-sided advertising. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13(4), 454-463.

Ready to

make your brand

irresistible?